Chinese classifier

In the modern Chinese languages, words known as classifiers or measure words (simplified Chinese: 量词; traditional Chinese: 量詞; pinyin: liàngcí) are used along with numbers to define the quantity of a given object, or with demonstratives such as "this" and "that" to identify specific objects. Classifiers are bound morphemes: they do not have any meaning by themselves and are always used in conjunction with a noun or another content word. Whenever a noun is preceded by a number or a demonstrative, a classifier must come in between. The choice whether to use a number or demonstrative at all, however, is up to the speaker; classifiers may often be avoided by simply using a bare noun. Phrases consisting of a number, a classifier, and a noun, such as 一个人 (yí ge rén, one-CL person), are known as "classifier phrases". Some linguists have proposed that the use of classifier phrases may be guided less by grammar and more by stylistic or pragmatic concerns on the part of a speaker who may be trying to foreground new or important information. Finally, in addition to these uses, classifiers may be used in variant ways: when placed after a noun rather than before it, or when repeated, a classifier signifies a plural or indefinite quantity.

Most nouns have one or more particular classifiers associated with them. For example, many flat objects such as tables, papers, beds, and benches use the classifier 张 (張) zhāng, whereas many long and thin objects use 条 (條) tiáo. The way speakers choose which classifiers to use—and thus, by extension, how nouns are categorized—has been the subject of debate. Some propose that classifier–noun pairings are based on innate semantic features of the noun (for example, all "long" nouns take a certain classifier because of their inherent longness), and others claim that they are motivated by analogy to more prototypical pairings (for example, "dictionary" takes the same classifier as the more common word "book"). In addition to these specific classifiers, there is a general classifier 个 (個), pronounced gè in Mandarin, that may often (but not always) be used in place of other classifiers; in informal and spoken language, native speakers tend to use this classifier far more than any other, even though they know which classifier is "correct" when asked. Finally, Chinese also has mass-classifiers, or words that are not specific to any one object; for example, the mass-classifier 盒 (hé, box) may be used with boxes of objects, such as lightbulbs or books, even though those nouns also have their own special classifiers. In all, Chinese has anywhere from a few dozen to several hundred classifiers, depending on how they are counted; there is also variation in which classifiers are paired to which nouns, with speakers of different dialects often using different classifiers for the same item.

Many languages close to Chinese exhibit similar classifier systems, leading to speculation about the origins of the Chinese system. Ancient classifier-like constructions, which used a repeated noun rather than a special classifier, are attested in Chinese as early as 1400 BCE, but true classifiers did not appear in these phrases until much later. Originally, classifiers and numbers came after the noun rather than before, and probably moved before the noun sometime after 500 BCE. The use of classifiers did not become a mandatory part of Chinese grammar until around 1100 CE. Some nouns became associated with specific classifiers earlier than others, the earliest probably being nouns that signified culturally valued items such as horses and poems. Many words that are classifiers today started out as full nouns, and their meanings were gradually bleached away until they could only be used as classifiers.

Contents |

Usage

In Chinese, a numeral cannot quantify a noun by itself; instead, the language relies on classifiers, commonly referred to as measure words.[note 1] When a noun is preceded by a number, a demonstrative such as this or that, or a quantifier such as every, a classifier mandatorily appears directly before the noun.[1] Thus, while English speakers say "one person" or "this person", Chinese speakers say respectively 一个人 (yí ge rén, one-CL person) or 这个人 (zhè ge rén, this-CL person). If a noun is preceded by both a demonstrative and a number, the demonstrative comes first.[2] (This is just as in English, e.g. "these three cats".) If an adjective modifies the noun, it comes after the classifier and before the noun. The general structure of a classifier phrase is

demonstrative – number – classifier – adjective – noun

The tables below give examples of common types of classifier phrases.[3] While most English nouns do not need classifiers (special, rare phrases like "five head of cattle" do, but most ordinary phrases such as "three cats" do not), all Chinese nouns do; thus, in the first table, phrases that have no classifier in English have one in Chinese.

| demonstrative | number | classifier | adjective | noun | English equivalent | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NUM-CL-N | three |

CL |

cat |

"three cats" | |||

| DEM-CL-N | this |

CL |

cat |

"this cat" | |||

| NUM-CL | three |

CL |

"three"* | ||||

| NUM-CL-ADJ-N | three |

CL |

black |

cat |

"three black cats" | ||

| DEM-NUM-CL-ADJ-N | this |

three |

CL |

black |

cat |

"these three black cats" | |

| NUM-CL-ADJ | three |

CL |

black |

"three black ones"* | |||

| * When "cats" is already evident from the context, as in "How many cats do you have?" "I have three." ** When an adjective in Chinese appears by itself, with no noun after it, 的 is added. The use of 的 in this example is not related to the presence of classifiers. |

|||||||

| demonstrative | number | classifier | adjective | noun | English equivalent | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NUM-CL-N | five |

CL |

cattle |

"five head of cattle" | |||

| DEM-CL-N | this |

CL |

cattle |

"this head of cattle" | |||

| NUM-CL | five |

CL |

"five head"* | ||||

| NUM-CL-ADJ-N | five |

CL |

big |

cattle |

"five head of big cattle" | ||

| DEM-NUM-CL-ADJ-N | this |

five |

CL |

big |

cattle |

"these five head of big cattle" | |

| NUM-CL-ADJ | five |

CL |

big |

"five head of big ones"* | |||

| * When "cattle" is already evident from the context, as in "How many cattle do you have?" "I have five head." ** When an adjective in Chinese appears by itself, with no noun after it, 的 is added. The use of 的 in this example is not related to the presence of classifiers. |

|||||||

On the other hand, when a noun is not counted or introduced with a demonstrative, a classifier is not necessary: for example, there is a classifier in 三辆车 (sān liàng chē, three-CL car, "three cars") but not in 我的车 (wǒ-de chē, me-possessive car, "my car").[4] Furthermore, numbers and demonstratives are often not required in Chinese, so speakers may choose not to use one—and thus not to use a classifier. For example, to say "Zhangsan turned into a tree", both 张三变成了一棵树 (Zhāngsān biànchéng -le yí kè shù, Zhangsan become PAST one CL tree) and 张三变成了树 (Zhāngsān biànchéng -le shù, Zhangsan become PAST tree) are acceptable.[5]

Specialized uses

In addition to their uses with numbers and demonstratives, classifiers have some other functions. A classifier placed after a noun expresses a plural or indefinite quantity of it. For example, 书本 (shū-běn, book-CL) means "the books" (e.g., on a shelf, or in a library), whereas the standard pre-nominal construction 一本书 (yì běn shū, one-CL book) means "one book".[6]

Many classifiers may be reduplicated to mean "every". For example, 个个人 (gè-ge rén, CL-CL person) signifies "every person".[7]

Finally, a classifier used along with 一 (yī, "one") and after a noun conveys a meaning close to "all of" or "the entire" or "a ___ful of".[8] The sentence 天空一片云 (tiānkōng yí piàn yún, sky one-CL cloud), meaning "the sky was full of clouds", uses the classifier 片 (piàn, slice), which refers to the sky, not the clouds.[note 2]

Types

The vast majority of classifiers are those that count or classify nouns.[9] These are further subdivided into count-classifiers and mass-classifiers, described below. In everyday speech, people often use the term "measure word", or its literal Chinese equivalent 量词 liàngcí, to cover all Chinese classifiers and mass-classifiers,[10] but the types of words grouped under this term are not all the same. Specifically, the various types of classifiers exhibit numerous differences in meaning, in the kinds of words they attach to, and in syntactic behavior.

Chinese has a large number of nominal classifiers; estimates of the number in Mandarin range from "several dozen"[11] or "about 50",[12] to over 900.[13] The range is so large because some of these estimates include all types of classifiers while others include only count-classifiers,[note 3] and because the idea of what constitutes a "classifier" has changed over time. Today, regular dictionaries include 120 to 150 classifiers;[14] the 8822-word Syllabus of Graded Words and Characters for Chinese Proficiency[note 4] (Chinese: 汉语水平词汇与汉字等级大纲; pinyin: Hànyǔ Shuǐpíng Cíhuì yú Hànzi Děngjí Dàgāng) lists 81;[15] and a 2009 list compiled by Gao Ming and Barbara Malt includes 126.[16] The number of classifiers that are in everyday, informal use, however, may be lower: linguist Mary Erbaugh has claimed that about two dozen "core classifiers" account for most classifier use.[17] As a whole, though, the classifier system is so complex that specialized classifier dictionaries have been published.[16][note 5]

Count-classifiers and mass-classifiers

A classifier categorizes a class of nouns by picking out some salient perceptual properties...which are permanently associated with entities named by the class of nouns; a measure word does not categorize but denotes the quantity of the entity named by a noun.

Within the set of nominal classifiers, linguists generally draw a distinction between "count-classifiers" and "mass-classifiers". True count-classifiers[note 6] are used for naming or counting a single count noun,[13] and have no direct translation in English; for example, 一本书 (yì běn shū, one-CL book) can only be translated in English as "one book" or "a book".[18] Furthermore, count-classifiers cannot be used with mass nouns: just as an English speaker cannot ordinarily say *"five muds", a Chinese speaker cannot say *五个泥 (wǔ ge nì, five-CL mud). For such mass nouns, one must use mass-classifiers.[13][note 7]

Mass-classifiers (true measure words) do not pick out inherent properties of an individual noun like count-classifiers do; rather, they lump nouns into countable units. Thus, mass-classifiers can generally be used with multiple types of nouns; for example, while the mass-classifier 盒 (hé, box) can be used to count boxes of lightbulbs (一盒灯泡 yì hé dēngpào, "one box of lightbulbs") or of books (一盒教材 yì hé jiàocái, "one box of textbooks"), each of these nouns must use a different count-classifier when being counted by itself (一盏灯泡 yì zhǎn dēngpào "one lightbulb"; vs. 一本教材 yì běn jiàocái "one textbook"). While count-classifiers have no direct English translation, mass-classifiers often do: phrases with count-classifiers such as 一个人 (yí ge rén, one-CL person) can only be translated as "one person" or "a person", whereas those with mass-classifiers such as 一群人 (yì qún rén, one-crowd-person) can be translated as "a crowd of people". All languages, including English, have mass-classifiers, but count-classifiers are unique to certain "classifier languages", and are not a part of English grammar apart from a few exceptional cases such as head of livestock.[19]

Within the range of mass-classifiers, authors have proposed subdivisions based on the manner in which a mass-classifier organizes the noun into countable units. One of these is measurement units (also called "standard measures"),[20] which all languages must have in order to measure items; this category includes units such as kilometers, liters, or pounds.[21] Like other classifiers, these can also stand without a noun; thus, for example, 磅 (bàng, pound) may appear as both 三磅肉 (sān bàng ròu, "three pounds of meat") or just 三磅 (sān bàng, "three pounds", never *三个磅 sān ge bàng).[22] Other proposed types of mass-classifiers include "collective"[23][note 8] mass-classifiers, such as 一群人 (yì qún rén, "a crowd of people"), which group things less precisely; and "container"[24] mass-classifiers, which group things by containers they come in, as in 一碗粥 (yì wǎn zhōu, "a bowl of porridge") or 一包糖 (yì bāo táng, "a bag of sugar").

While mass-classifiers are universal, count-classifiers only appear in certain languages.[19] The difference between count-classifiers and mass-classifiers can be described as one of quantifying versus categorizing: in other words, mass-classifiers create a unit by which to measure something (i.e., boxes, groups, chunks, pieces, etc.), whereas count-classifiers simply name an existing item.[25] Most words can appear with both count-classifiers and mass-classifiers; for example, pizza can be described as both 一张比萨 (yì zhāng bǐsà, "one pizza", literally "one pie of pizza"), using a count-classifier, and as 一块比萨 (yí kuài bǐsà, "one piece of pizza"), using a mass-classifier. In addition to these semantic differences, there are differences in the grammatical behaviors of count-classifiers and mass-classifiers;[26] for example, mass-classifiers may be modified by a small set of adjectives (as in 一大群人 yí dà qún rén, "a big crowd of people"), whereas count-classifiers usually may not (for example, *一大个人 yí dà ge rén is never said for "a big person"; instead the adjective must modify the noun: 一个大人 yí ge dà rén).[27] Another difference is that count-classifiers may often be replaced by a "general" classifier 个 (個), gè with no apparent change in meaning, whereas mass-classifiers may not.[28] Syntacticians Lisa Cheng and Rint Sybesma propose that count-classifiers and mass-classifiers have different underlying syntactic structures, with count-classifiers forming "classifier phrases",[note 9] and mass-classifiers being a sort of relative clause that only looks like a classifier phrase.[29] The distinction between count-classifiers and mass-classifiers is often unclear, however, and other linguists have suggested that count-classifiers and mass-classifiers may not be fundamentally different. They posit that "count-classifier" and "mass-classifier" are the extremes of a continuum, with most classifiers falling somewhere in between.[30]

Verbal classifiers

There is a set of "verbal classifiers" used for counting the number of times an action occurs, rather than counting a number of items; this set includes 次 cì, 遍 biàn, 回 huí, and 下 xià, which all roughly translate to "times".[31] For example, 我去过三次北京 (wǒ qù-guo sān cì Běijīng, I go-PAST three-CL Beijing, "I have been to Beijing three times") uses a so-called "verbal classifier".[32] Beyond these verb-only classifiers, however, the division of classifiers into "verbal" and "nominal" is controversial.[33] Qian Hu defines "verbal classifiers" as classifiers that "occur in a numerical noun phrase where the head noun is associated with an action"[34], and Charles Li and Sandra Thompson's Mandarin reference grammar lists them as essentially the same as nominal classifiers—in all their examples for 场 (場) chǎng, a general verbal classifier that can be used for classifying any events (such as ballgames, fires, and movies), the verbal classifier is used in the same way as a nominal classifier would be.[35]

Relation to nouns

鱼, yú

裤子, kùzi

河, hé

凳子, dèngzi

Different classifiers often correspond to different particular nouns. For example, books generally take the classifier 本 běn, flat objects take 张 (張) zhāng, animals take 只 (隻) zhī, machines take 台 tái, large buildings and mountains take 座 zuò, etc. Within these categories are further subdivisions—while most animals take 只 (隻) zhī, domestic animals take 头 (頭) tóu, long and flexible animals take 条 (條) tiáo, and horses take 匹 pǐ. Likewise, while long things that are flexible (such as ropes) often take 条 (條) tiáo, long things that are rigid (such as sticks) take 根 gēn, unless they are also round (like pens or cigarettes), in which case in some dialects they take 枝 zhī.[37] Classifiers also vary in how specific they are; some (such as 朵 duǒ for flowers) are generally only used with one item, whereas others (such as 条 (條) tiáo for long and flexible things, one-dimensional things, or abstract items like news reports)[note 10] are much less restricted.[38] Furthermore, there is not a one-to-one relationship between nouns and classifiers: the same noun may be paired with different classifiers in different situations.[39] The specific factors that govern which classifiers are paired with which nouns have been a subject of debate among linguists.

Categories and prototypes

While mass-classifiers do not necessarily bear any semantic relationship to the noun with which they are used (e.g., box and book are not related in meaning, but one can still say "a box of books"), count-classifiers do.[29] The precise nature of that relationship, however, is not certain, since there is so much variability in how objects may be organized and categorized by classifiers. Accounts of the semantic relationship may be grouped loosely into categorical theories, which propose that count-classifiers are matched to objects solely on the basis of inherent features of those objects (such as length or size), and prototypical theories, which propose that people learn to match a count-classifier to a specific prototypical object and to other objects that are like that prototype.[40]

The categorical, "classical"[41] view of classifiers was that each classifier represents a category with a set of conditions; for example, the classifier 条 (條) tiáo would represent a category defined as all objects that meet the conditions of being long, thin, and one-dimensional—and nouns using that classifier must fit all the conditions with which the category is associated. Some common semantic categories into which count-classifiers have been claimed to organize nouns include the categories of shape (long, flat, or round), size (large or small), consistency (soft or hard), animacy (human, animal, or object),[42] and function (tools, vehicles, machines, etc.).[43]

On the other hand, proponents of prototype theory propose that count-classifiers may not have innate definitions, but are associated with a noun that is prototypical of that category, and nouns that have a "family resemblance" with the prototype noun will want to use the same classifier.[note 11] For example, horse in Chinese uses the classifier 匹 pǐ, as in 三匹马 (sān pǐ mǎ, "three horses")—in modern Chinese the word 匹 has no meaning. Nevertheless, nouns denoting animals that look like horses will often also use this same classifier, and native speakers have been found to be more likely to use the classifier 匹 the closer an animal looks to a horse.[44] Furthermore, words that do not meet the "criteria" of a semantic category may still use that category because of their association with a prototype. For example, the classifier 颗 (顆) kè is used for small round items, as in 一颗子弹 (yì kē zǐdàn, "one bullet"); when words like 原子弹 (yuánzǐdàn, "atomic bomb") were later introduced into the language they also used this classifier, even though they are not small and round—therefore, their classifier must have been assigned because of the words' association with the word for bullet, which acted as a "prototype".[45] This is an example of "generalization" from prototypes: Erbaugh has proposed that when children learn count-classifiers, they go through stages, first learning a classifier-noun pair only (such as 条鱼 tiáo yú, CL-fish), then using that classifier with multiple nouns that are similar to the prototype (such as other types of fish), then finally using that set of nouns to generalize a semantic feature associated with the classifier (such as length and flexibility) so that the classifier can then be used with new words that the person encounters.[46]

Some classifier-noun pairings are arbitrary, or at least appear to modern speakers to have no semantic motivation.[47] For instance, the classifier 部 bù may be used for movies and novels, but also for cars[48] and telephones.[49] Some of this arbitrariness may be due to what linguist James Tai refers to as "fossilization", whereby a count-classifier loses its meaning through historical changes but remains paired with some nouns. For example, the classifier 匹 pǐ used for horses is meaningless today, but in Classical Chinese may have referred to a "team of two horses",[50] a pair of horse skeletons,[51] or the pairing between man and horse.[52][note 12] Arbitrariness may also arise when a classifier is borrowed, along with its noun, from a dialect in which it has a clear meaning to one in which it does not.[53] In both these cases, the use of the classifier is remembered more by association with certain "prototypical" nouns (such as horse) rather than by understanding of semantic categories, and thus arbitrariness has been used as an argument in favor of the prototype theory of classifiers.[53] Gao and Malt propose that both the category and prototype theories are correct: in their conception, some classifiers constitute "well-defined categories", others make "prototype categories", and still others are relatively arbitrary.[54]

Neutralization

In addition to the numerous "specific" count-classifiers described above,[note 13] Chinese has a "general" classifier 个 (個), pronounced gè in Mandarin.[note 14] This classifier is used for people, some abstract concepts, and other words that do not have special classifiers (such as 汉堡包 hànbǎobāo "hamburger"),[55] and may also be used as a replacement for a specific classifier such as 张 (張) zhāng or 条 (條) tiáo, especially in informal speech. It has been noted as early as the 1940s that the use of 个 is increasing and that there is a general tendency towards replacing specific classifiers with it.[56] Numerous studies have reported that both adults and children tend to use 个 when they do not know the appropriate count-classifier, and even when they do but are speaking quickly or informally.[57] The replacement of a specific classifier with the general 个 is known as classifier neutralization[58] ("量词个化" in Chinese, literally "classifier 个-ization"[59]). This occurs especially often among children[60] and aphasics (individuals with damage to language-relevant areas of the brain),[61][62] although normal speakers also neutralize frequently. It has been reported that most speakers know the appropriate classifiers for the words they are using and believe, when asked, that those classifiers are obligatory, but nevertheless use 个 without even realizing it in actual speech.[63] As a result, in everyday use the general classifier is "hundreds of times more frequent"[64] than the specialized ones.

Nevertheless, 个 has not completely replaced other count-classifiers, and there are still many situations in which it would be inappropriate to substitute it for the required specific classifier.[56] There may be specific patterns behind which classifier-noun pairs may be "neutralized" to use the general classifier, and which may not. Specifically, words that are most prototypical for their categories, such as paper for the category of nouns taking the "flat/square" classifier 张 (張) zhāng, may be less likely to be said with a general classifier.[65]

Variation in usage

|

|

|

|

A painting may be referred to with the classifiers 张 (張) zhāng and 幅 fú; both phrases have the same meaning, but convey different stylistic effects.[66]

|

Depending on the classifier used, the noun 楼 lóu could describe either this building, as in 一座楼 (yí zuò lóu "one building"), or the floors of the building, as in 二十层楼 (èrshí céng lóu, "twenty floors").[67]

|

There is no one-to-one pairing between count-classifiers and nouns. Across dialects and speakers there is great variability in the way classifiers are used for the same words, and speakers often do not agree which classifier is best.[68] For example, for cars some people use 部 bù, others use 台 tái, and still others use 辆 (輛) liàng; Cantonese uses 架 gaa3. Even within a single dialect or a single speaker, the same noun may take different measure words depending on the style in which the person is speaking, or on different nuances the person wants to convey (for instance, measure words can reflect the speaker's judgment of or opinion about the object[69]). An example of this is the word for person, 人 rén, which uses the measure word 个 (個) gè normally, but uses the measure 口 kǒu when counting number of people in a household, and 位 wèi when being particularly polite or honorific, and 名 míng in formal, written contexts;[70] likewise, a group of people may be referred to by massifiers as 一群人 (yì qún rén, "a group of people") or 一帮人 (yì bāng rén, "a gang/crowd of people"): the first is neutral, whereas the second implies that the people are unruly or otherwise being judged poorly.[71]

Some count-classifiers may also be used with nouns that they are not normally related to, for metaphorical effect, as in 一堆烦恼 (yí duì fánnǎo, "a pile of worries/troubles").[72] Finally, a single word may have multiple count-classifiers that convey different meanings altogether—in fact, the choice of a classifier can even influence the meaning of a noun. By way of illustration, 三节课 sān jié kè means "three class periods" (as in "I have three classes today"), whereas 三门课 sān mén kè means "three courses" (as in "I signed up for three courses this semester"), even though the noun in each sentence is the same.[67]

Purpose

In research on classifier systems, and Chinese classifiers in particular, linguists have asked why count-classifiers (as opposed to mass-classifiers) exist at all. Mass-classifiers are present in all languages since they are the only way to "count" mass nouns that are not naturally divided into units (as, for example, "three splotches of mud" in English; *"three muds" is ungrammatical). On the other hand, count-classifiers are not inherently mandatory, and are absent from most languages.[19][note 15] Furthermore, count-classifiers are used with an "unexpectedly low frequency";[73] in many settings, speakers avoid specific classifiers by just using a bare noun (without a number or demonstrative) or using the general classifier 个 gè.[74] Linguists and typologists such as Joseph Greenberg have suggested that specific count-classifiers are semantically "redundant", repeating information present within the noun.[75] Count-classifiers can be used stylistically, though,[70] and can also be used to clarify or limit a speaker's intended meaning when using a vague or ambiguous noun; for example, the noun 课 kè "class" can refer to courses in a semester or specific class periods during a day, depending on whether the classifier 门 (門) mén or 节 (節) jié is used.[76]

One proposed explanation for the existence of count-classifiers is that they serve more of a cognitive purpose than a practical one: in other words, they provide a linguistic way for speakers to organize or categorize real objects.[77] An alternate account is that they serve more of a discursive and pragmatic function (a communicative function when people interact) rather than an abstract function within the mind.[74] Specifically, it has been proposed that count-classifiers might be used to mark new or unfamiliar objects within a discourse,[77] to introduce major characters or items in a story or conversation,[78] or to foreground important information and objects by making them bigger and more salient.[79] In this way, count-classifiers might not serve an abstract grammatical or cognitive function, but may help in communication by making important information more noticeable and drawing attention to it.

History

Classifier phrases

Historical linguists have found that phrases consisting of nouns and numbers went through several structural changes in Old Chinese and Middle Chinese before classifiers appeared in them. The earliest forms may have been Number – Noun, like English (i.e., "five horses"), and the less common Noun – Number ("horses five"), both of which are attested in the oracle bone scripts of Pre-Archaic Chinese (circa 1400 BCE to 1000 BCE).[80] The first constructions resembling classifier constructions were Noun – Number – Noun constructions, which were also extant in Pre-Archaic Chinese but less common than Number – Noun. In these constructions, sometimes the first and second nouns were identical (N1 – Number – N1, as in "horses five horses") and other times the second noun was different, but semantically related (N1 – Number – N2). According to some historical linguists, the N2 in these constructions can be considered an early form of count-classifier and has even been called an "echo classifier"; this speculation is not universally agreed on, though.[81] Although true count-classifiers had not appeared yet, mass-classifiers were common in this time, with constructions such as "wine – six – yǒu" (the word 酉 yǒu represented a wine container) meaning "six yǒu of wine".[81] Examples such as this suggest that mass-classifiers predate count-classifiers by several centuries, although they did not appear in the same word order as they do today.[82]

It is from this type of structure that count-classifiers may have arisen, originally replacing the second noun (in structures where there was a noun rather than a mass-classifier) to yield Noun – Number – Classifier. That is to say, constructions like "horses five horses" may have been replaced by ones like "horses five CL", possibly for stylistic reasons such as avoiding repetition.[83] Another reason for the appearance of count-classifiers may have been to avoid confusion or ambiguity that could have arisen from counting items using only mass-classifiers—i.e., to clarify when one is referring to a single item and when one is referring to a measure of items.[84]

Historians agree that at some point in history the order of words in this construction shifted, putting the noun at the end rather than beginning, like in the present-day construction Number – Classifier – Noun.[85] According to historical linguist Alain Peyraube, the earliest occurrences of this construction (albeit with mass-classifiers, rather than count-classifiers) appear in the late portion of Old Chinese (500 BCE to 200 BCE). At this time, the Number – Mass-classifier portion of the Noun – Number – Mass-classifier construction is was sometimes shifted in front of the noun. Peyraube speculates that this may have occurred because it was gradually reanalyzed as a modifier (like an adjective) for the head noun, as opposed to a simple repetition as it originally was. Since Chinese generally places modifiers before modified, as does English, the shift may have been prompted by this reanalysis. By the early part of the Common Era, the nouns appearing in "classifier position" were beginning to lose their meaning and become true classifiers. Estimates of when classifiers underwent the most development vary: Wang Li claims their period of major development was during the Han Dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE),[86] whereas Liu Shiru estimates that it was the Southern and Northern Dynasties period (420 – 589 CE),[87] and Peyraube chooses the Tang Dynasty (618 – 907 CE).[88] Regardless of when they developed, Wang Lianqing claims that they did not become grammatically mandatory until sometime around the 11th century.[89]

Classifier systems in many nearby languages and language groups (such as Vietnamese and the Tai languages) are very similar to the Chinese classifier system in both grammatical structure and the parameters along which some objects are grouped together. Thus, there has been some debate over which language family first developed classifiers and which ones then borrowed them—or whether classifier systems were native to all these languages and developed more through repeated language contact throughout history.[90]

Classifier words

Most modern count-classifiers are derived from words that originally were free-standing nouns in older varieties of Chinese, and have since been grammaticalized to become bound morphemes.[91] In other words, count-classifiers tend to come from words that once had specific meaning but lost it (a process known as semantic bleaching).[92] Many, however, still have related forms that work as nouns all by themselves, such as the classifier 带 (帶) dài for long, ribbon-like objects: the modern word 带子 dàizi means "ribbon".[72] In fact, the majority of classifiers can also be used as other parts of speech, such as nouns.[93] Mass-classifiers, on the other hand, are more transparent in meaning than count-classifiers; while the latter have some historical meaning, the former are still full-fledged nouns. For example, 杯 (bēi, cup), is both a classifier as in 一杯茶 (yì bēi chá, "a cup of tea") and the word for a cup as in 酒杯 (jiǔbēi, "wine glass").[94]

Where do these classifiers come from? Each classifier has its own history.

It may not have always been the case that every noun required a count-classifier. In many historical varieties of Chinese, use of classifiers was not mandatory, and classifiers are rare in writings that have survived.[95] Some nouns acquired classifiers earlier than others; some of the first documented uses of classifiers were for inventorying items, both in mercantile business and in storytelling.[96] Thus, the first nouns to have count-classifiers paired with them may have been nouns that represent "culturally valued" items such as horses, scrolls, and intellectuals.[97] The special status of such items is still apparent today: many of the classifiers that can only be paired with one or two nouns, such as 匹 pǐ for horses[note 16] and 首 shǒu for songs or poems, are the classifiers for these same "valued" items. Such classifiers make up as much as one-third of the commonly used classifiers today.[17]

Classifiers did not gain official recognition as a lexical category (part of speech) until the 20th century. The earliest modern text to discuss classifiers and their use was Ma Jianzhong's 1898 Ma's Basic Principles for Writing Clearly (马氏文通).[98] From then until the 1940s, linguists such as Ma, Wang Li, and Li Jinxi treated classifiers as just a type of noun that "expresses a quantity".[86] Lü Shuxiang was the first to treat them as a separate category, calling them "unit words" (单位词 dānwèicí) in his 1940s Outline of Chinese Grammar (中国文法要略) and finally "measure words" (量词 liàngcí) in Grammar Studies (语法学习). He made this separation based on the fact that classifiers were semantically bleached, and that they can be used directly with a number, whereas true nouns need to have a measure word added before they can be used with a number.[99] After this time, other names were also proposed for classifiers: Gao Mingkai called them "noun helper words" (助名词 zhùmíngcí), Lu Wangdao "counting markers" (计标 jìbiāo), and Japanese linguist Miyawaki Kennosuke called them "accompanying words" (陪伴词 péibàncí).[100] In the Draft Plan for a System of Teaching Chinese Grammar (暂拟汉语教学语法系统) adopted by the People's Republic of China in 1954, Lü's "measure words" (量词 liàngcí) was adopted as the official name for classifiers in China.[101] This remains the most common term in use today.[10]

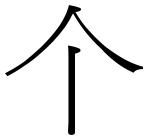

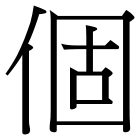

General classifiers

Historically, 个 gè was not always the general classifier. Some believe it was originally a noun referring to bamboo stalks, and gradually expanded in use to become a classifier for many things with "vertical, individual, [or] upright qualit[ies]",[102] eventually becoming a general classifier because it was used so frequently with common nouns.[103] The classifier gè is actually associated with three different homophonous characters: 个, 個 (used today as the traditional-character equivalent of 个), and 箇. Historical linguist Lianqing Wang has argued that these characters actually originated from different words, and that only 箇 had the original meaning of "bamboo stalk".[104] 个, she claims, was used as a general classifier early on, and may have been derived from the orthographically similar 介 jiè, one of the earliest general classifiers.[105] 箇 later merged with 介 because they were similar in pronunciation and meaning (both used as general classifiers).[104] Likewise, she claims that 個 was also a separate word (with a meaning having to do with "partiality" or "being a single part"), and merged with 个 for the same reasons as 箇 did; she also argues that 個 was "created", as early as the Han Dynasty, to supersede 个.[106]

Nor was 个 the only general classifier in the history of Chinese. The aforementioned 介 jiè was being used as a general classifier before the Qin Dynasty (221 BCE); it was originally a noun referring to individual items out of a string of connected shells or clothes, and eventually came to be used as a classifier for "individual" objects (as opposed to pairs or groups of objects) before becoming a general classifier.[107] Another general classifier was 枚 méi, which originally referred to small twigs. Since twigs were used for counting items, 枚 became a counter word: any items, including people, could be counted as "one 枚, two 枚", etc. 枚 was the most common classifier in use during the Southern and Northern Dynasties period (420–589 CE),[108] but today is no longer a general classifier, and is only used rarely, as a specialized classifier for pins and badges.[109] Kathleen Ahrens has claimed that 隻 (zhī in Mandarin and jia in Taiwanese), the classifier for animals in Standard Mandarin, is another general classifier in Taiwanese and may be becoming one in the Mandarin spoken in Taiwan.[110]

See also

- List of Chinese classifiers

- Chinese grammar

- Collective noun

- Classifiers in other languages:

- Burmese numerical classifiers

- Japanese counter word

- Korean counter word

- Vietnamese classifier

Notes

- ↑ Across different varieties of Chinese, classifier-noun clauses have slightly different interpretations (particularly in the interpretation of definiteness in classified nouns as opposed to bare nouns), but the requirement that a classifier come between a number and a noun is more or less the same in the major varieties (Cheng & Sybesma 2005).

- ↑ See, for example, similar results in the Chinese corpus of the Center for Chinese Linguistics at Peking University: 天空一片, retrieved on 3 June 2009.

- ↑ In addition to the count-mass distinction and nominal-verbal distinction described below, various linguists have proposed many additional divisions of classifiers by type. He (2001, chapters 2 and 3) contains a review of these.

- ↑ The Syllabus of Graded Words and Characters for Chinese Proficiency is a standardized measure of vocabulary and character recognition, used in the People's Republic of China for testing middle school students, high school students, and foreign learners. The most recent edition was published in 2003 by the Testing Center of the National Chinese Proficiency Testing Committee.

- ↑ Including the following:

- Chen, Baocun (陈保存) (1988). Chinese Classifier Dictionary (汉语量词词典). Fuzhou: Fujian People's Publishing House (福建人民出版社). ISBN 9787211003754

- Fang, Jiqing; Connelly; Michael (2008). Chinese Measure Word Dictionary. Boston: Cheng & Tsui. ISBN 0887276326

- Jiao, Fan (焦凡) (2001). A Chinese-English Dictionary of Measure Words (汉英量词词典). Beijing: Sinolingua (华语敎学出版社). ISBN 9787800525681

- Liu, Ziping (刘子平) (1996). Chinese Classifier Dictionary (汉语量词词典). Inner Mongolia Education Press (内蒙古教育出版社). ISBN 9787531127079

- ↑ Count-classifiers have also been called "individual classifiers", (Chao 1968, p. 509), "qualifying classifiers" (Zhang 2007, p. 45; Hu 1993, p. 10), and just "classifiers" (Cheng & Sybesma 1998, p. 3).

- ↑ Mass-classifiers have also been called "measure words", "massifiers" (Cheng & Sybesma 1998, p. 3), "non-individual classifiers" (Chao 1968, p. 509), and "quantifying classifiers" (Zhang 2007, p. 45; Hu 1993, p. 10). The term "mass-classifier" is used in this article to avoid ambiguous usage of the term "measure word", which is often used in everyday speech to refer to both count-classifiers and mass-classifiers, even though in technical usage it only means mass-classifiers (Li 2000, p. 1116).

- ↑ Also called "aggregate" (Li & Thompson 1981, pp. 107–109) or "group" (Ahrens 1994, p. 239, note 3) measures.

- ↑ "Classifier phrases" are similar to noun phrases, but with a classifier rather than a noun as the head (Cheng & Sybesma 1998, pp. 16–17).

- ↑ This may be because official documents during the Han Dynasty were written on long bamboo strips, making them "strips of business" (Ahrens 1994, p. 206).

- ↑ The theory described in Ahrens (1994) and Wang (1994) is also referred to within those works as a "prototype" theory, but differs somewhat from the version of prototype theory described here; rather than claiming that individual prototypes are the source for classifier meanings, these authors believe that classifiers still are based on categories with features, but that the categories have many features, and "prototypes" are words that have all the features of that category whereas other words in the category only have some features. In other words, "there are core and marginal members of a category.... a member of a category does not necessarily possess all the properties of that category" (Wang 1994, p. 8). For instance, the classifier 棵 kè is used for the category of trees, which may have features such as "has a trunk", "has leaves", and "has branches", "is deciduous"; maple trees would be prototypes of the category, since they have all these features, whereas palm trees only have a trunk and leaves and thus are not prototypical (Ahrens 1994, pp. 211–12).

- ↑ The apparent disagreement between the definitions provided by different authors may reflect different uses of these words in different time periods. It is well-attested that many classifiers underwent frequent changes of meaning throughout history (Wang 1994; Erbaugh 1986, pp. 426–31; Ahrens 1994, pp. 205–206), so 匹 pǐ may have had all these meanings at different points in history.

- ↑ Also called "sortal classifiers" (Erbaugh 2000, p. 33; Biq 2002, p. 531).

- ↑ Kathleen Ahrens claimed in 1994 that the classifier for animals—隻, pronounced zhī in Mandarin and jia in Taiwanese—is in the process of becoming a second general classifier in the Mandarin spoken in Taiwan, and already is used as the general classifier in Taiwanese itself (Ahrens 1994, p. 206).

- ↑ Although English does not have a productive system of count-classifiers and is not considered a "classifier language", it does have a few constructions—mostly archaic or specialized—that resemble count-classifiers, such as "X head of cattle" (T'sou 1976, p. 1221).

- ↑ Today, 匹 may also be used for bolts of cloth. See "List of Common Nominal Measure Words" on ChineseNotes.com (last modified 11 January 2009; retrieved on 3 September 2009).

References

- ↑ Li & Thompson 1981, p. 104

- ↑ Hu 1993, p. 13

- ↑ The examples are adapted from those given in Hu (1993, p. 13), Erbaugh (1986, pp. 403–404), and Li & Thompson (1981, pp. 104–105).

- ↑ Zhang 2007, p. 47

- ↑ Li 2000, p. 1119

- ↑ Li & Thompson 1981, p. 82

- ↑ Li & Thompson 1981, pp. 34–35

- ↑ Li & Thompson 1981, p. 111

- ↑ Hu 1993, p. 9

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Li 2000, p. 1116; Hu 1993, p. 7; Wang 1994, pp. 22, 24–25; He 2001, p. 8. Also see the usage in Fang & Connelly (2008) and most introductory Chinese textbooks.

- ↑ Li & Thompson 1981, p. 105

- ↑ Chao 1968, section 7.9

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Zhang 2007, p. 44

- ↑ Erbaugh 1986, p. 403; Fang & Connelly 2008, p. ix

- ↑ He 2001, p. 234

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Gao & Malt 2009, p. 1133

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Erbaugh 1986, p. 403

- ↑ Erbaugh 1986, p. 404

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Tai 1994, p. 3; Allan 1997, pp. 285–86; Wang 1994, p. 1

- ↑ Ahrens 1994, p. 239, note 3

- ↑ Li & Thompson 1981, p. 105; Zhang 2007, p. 44; Erbaugh 1986, p. 118, note 5

- ↑ Li & Thompson 1981, pp. 105–107

- ↑ Erbaugh 1986, p. 118, note 5; Hu 1993, p. 9

- ↑ Erbaugh 1986, p. 118, note 5; Li & Thompson 1981, pp. 107–109

- ↑ Cheng & Sybesma 1998, p. 3; Tai 1994, p. 2

- ↑ Wang 1994, pp. 27–36; Cheng & Sybesma 1998

- ↑ Cheng & Sybesma 1998, pp. 3–5

- ↑ Wang 1994, p. 29–30

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Cheng & Sybesma 1998

- ↑ Ahrens 1994, p. 239, note 5; Wang 1994, pp. 26–27, 37–48

- ↑ He 2001, pp. 42, 44

- ↑ Zhang 2007, p. 44; Li & Thompson 1981, p. 110; Fang & Connelly 2008, p. x

- ↑ He 2001, p. 30

- ↑ Hu 1993, p. 7

- ↑ Li & Thompson 1981, p. 110

- ↑ Tai 1994, p. 8

- ↑ Tai 1994, p. 7–9; Tai & Wang 1990

- ↑ Erbaugh 1986, p. 111

- ↑ He 2001, p. 239

- ↑ Tai 1994, pp. 3–5; Ahrens 1994, pp. 208–12

- ↑ Tai 1994, p. 3; Ahrens 1994, pp. 209–10

- ↑ Tai 1994, p. 5; Allan 1977

- ↑ Hu 1993, p. 1

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Tai 1994, p. 12

- ↑ Zhang 2007, pp. 46–47

- ↑ Erbaugh 1986, p. 415

- ↑ Hu 1993, p. 1; Tai 1994, p. 13; Zhang 2007, pp. 55–56

- ↑ Zhang 2007, pp. 55–56

- ↑ Gao & Malt 2009, p. 1134

- ↑ Morev 2000, p. 79

- ↑ Wang 1994, pp. 172–73

- ↑ Tai 1994, p. 15, note 7

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 Tai 1994, p. 13

- ↑ Gao & Malt 2009, p. 1133–4

- ↑ Hu 1993, p. 12

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 Tzeng, Chen & Hung 1991, p. 193

- ↑ Zhang 2007, p. 57

- ↑ Ahrens 1994, p. 212

- ↑ He 2001, p. 165

- ↑ Erbaugh 1986; Hu 1993

- ↑ Ahrens 1994, pp. 227–32

- ↑ Tzeng, Chen & Hung 1991

- ↑ Erbaugh 1986, pp. 404–406; Ahrens 1994, pp. 202–203

- ↑ Erbaugh 1986, pp. 404–406

- ↑ Ahrens 1994

- ↑ Zhang 2007, p. 53

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 Zhang 2007, p. 52

- ↑ Tai 1994; Erbaugh 2000, pp. 34–35

- ↑ He 2001, p. 237

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 Fang & Connelly 2008, p. ix; Zhang 2007, pp. 53–54

- ↑ He 2001, p. 242

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 Shie 2003, p. 76

- ↑ Erbaugh 2000, p. 34

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 Erbaugh 2000, pp. 425–26; Li 2000

- ↑ Zhang 2007, p. 51

- ↑ Zhang 2007, pp. 51–52

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 Erbaugh 1986, p. 425–6

- ↑ Sun 1988, p. 298

- ↑ Li 2000

- ↑ Peyraube 1991, p. 107; Morev 2000, pp. 78–79

- ↑ 81.0 81.1 Peyraube 1991, p. 108

- ↑ Peyraube 1991, p. 110; Wang 1994, pp. 171–72

- ↑ Morev 2000, pp. 78–79

- ↑ Wang 1994, p. 172

- ↑ Peyraube 1991, p. 106; Morev 2000, pp. 78–79

- ↑ 86.0 86.1 He 2001, p. 3

- ↑ Wang 1994, pp. 2, 17

- ↑ Peyraube 1991, pp. 111–17

- ↑ Wang 1994, p. 3

- ↑ Erbaugh 1986, p. 401; Wang 1994, p. 2

- ↑ Shie 2003, p. 76; Wang 1994, pp. 113–14; 172–73

- ↑ Peyraube 1991, p. 116

- ↑ Gao & Malt 2009, p. 1130

- ↑ Chien, Lust & Chiang 2003, p. 92

- ↑ Peyraube 1991; Erbaugh 1986, p. 401

- ↑ Erbaugh 1986, p. 401

- ↑ Erbaugh 1986, pp. 401, 403, 428

- ↑ He 2001, p. 2

- ↑ He 2001, p. 4

- ↑ He 2001, pp. 5–6

- ↑ He 2001, p. 7

- ↑ Erbaugh 1986, p. 430

- ↑ Erbaugh 1986, pp. 428–30; Ahrens 1994, p. 205

- ↑ 104.0 104.1 Wang 1994, pp. 114–15

- ↑ Wang 1994, p. 95

- ↑ Wang 1994, pp. 115–16; 158

- ↑ Wang 1994, pp. 93–95

- ↑ Wang 1994, p. 155–7

- ↑ Erbaugh 1986, p. 428

- ↑ Ahrens 1994, p. 206

Bibliography

- Ahrens, Kathleen (1994). "Classifier production in normals and aphasics". Journal of Chinese Linguistics 2: 202–247.

- Allan, Keith (1977). "Classifiers". Language (Linguistic Society of America) 53 (2): 285–311. doi:10.2307/413103. http://jstor.org/stable/413103.

- Biq, Yung-O (2002). "Classifier and construction: the interaction of grammatical categories and cognitive strategies". Language and Linguistics 3 (3): 521–42.

- Chao, Yuen Ren (1968). A Grammar of Spoken Chinese. Berkeley: University of California Press

- Cheng, Lisa L.-S.; Sybesma, Rint (1998). "yi-wan tang and yi-ge Tang: Classifiers and mass-classifiers". Tsing Hua Journal of Chinese Studies 28 (3).

- Cheng, Lisa L.-S.; Sybesma, Rint (2005). "Classifiers in four varieties of Chinese". In Guglielmo Cinque, Richard S. Kayne. The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Syntax. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195136500

- Chien, Yu-Chin; Lust, Barbara; Chiang, Chi-Pang (2003). "Chinese children's comprehension of count-classifiers and mass-classifiers". Journal of East Asian Linguistics 12: 91–120. doi:10.1023/A:1022401006521.

- Erbaugh, Mary S. (1986). "Taking stock: the development of Chinese noun classifiers historically and in young children". In Colette Craig. Noun classes and categorization. J. Benjamins. 399–436. ISBN 9780915027330

- Erbaugh, Mary S. (2000). Classifiers are for specification: complementary functions for sortal and general classifiers in Cantonese and Mandarin. 33rd International Conference on Sino-Tibetan Languages and Linguistics.

- Fang, Jiqing; Connelly, Michael (2008). Chinese Measure Word Dictionary. Boston: Cheng & Tsui. ISBN 0887276326

- Gao, Ming; Malt, Barbara (2009). "Mental representation and cognitive consequences of Chinese individual classifiers". Language and Cognitive Processes 24 (7/8).

- He, Jie (何杰) (2001) (in Chinese). Studies on classifiers in Modern Chinese (现代汉语量词研究) (2nd ed.). Beijing: Nationalities Publishing House (民族出版社). ISBN 9787105047147

- Hsu, Natalie (2006). Issues in Head-final Relative Clauses in Chinese: Derivation, Processing, and Acquisition. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Delaware.

- Hu, Qian (1993). The acquisition of Chinese classifiers by young Mandarin-speaking children. Ph.D. dissertation, Boston University.

- Li, Charles N.; Thompson, Sandra A. (1981). Mandarin Chinese: A Functional Reference Grammar. Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520066106

- Li, Wendan (2000). "The pragmatic function of numeral-classifiers in Mandarin Chinese". Journal of Pragmatics 32: 1113–1133. doi:10.1016/S0378-2166(99)00086-7.

- Morev, Lev (2000). "Some afterthoughts on classifiers in the Tai languages". The Mon-Khmer Studies Journal 30: 75–82.

- Peyraube, Alain (1991). "Some remarks on the history of Chinese classifiers". In Patricia Marie Clancy, Sandra A. Thompson. Asian Discourse and Grammar. Linguistics. 3. 106–126

- Shie, Jian-Shiung (2003). "Figurative Extension of Chinese Classifiers". Journal of Da-Yeh University 12 (2): 73–83.

- Sun, Chaofen (1988). "The discourse function of numeral classifiers in Mandarin Chinese". Journal of Chinese Linguistics 2: 298–322.

- T'sou, Benjamin K. (1976). "The structure of nominal classifier systems". Oceanic Linguistics Special Publications, number 13. Austroasiatic Studies Part II. University of Hawai'i Press. 1215–1247

- Tai, James H.-Y. (1994). "Chinese classifier systems and human categorization". In Willian S.-Y. Wang, M. Y. Chen, and Ovid J.L. Tzeng. In honor of William S.-Y. Wang: Interdisciplinary studies on language and language change. Taipei: Pyramid Press. 479–494. ISBN 9789579268554

- Tai, James H.-Y.; Wang, Lianqing (1990). "A semantic study of the classifier tiao". Journal of the Chinese Language Teachers Association 25: 35–56.

- Wang, Lianqing (1994). Origin and development of classifiers in Chinese. Ph.D. dissertation, The Ohio State University.

- Zhang, Hong (2007). "Numeral classifiers in Mandarin Chinese". Journal of East Asian Linguistics 16: 43–59. doi:10.1007/s10831-006-9006-9.

External links

- List of Common Nominal Measure Words on chinesenotes.com

- Units of Weights and Measures on chinesenotes.com